|

Even before the creek dried out, the Putah Creek Council had a mess to clean up.

The wide, calm waters, memorialized in the riffs of John Fogerty’s "Green River," provided a reprieve from the relentless heat of Central Valley summers. But those same hidden banks and deep waters had turned the creek into a de facto town dump.

Mattresses, shopping carts and abandoned cars littered its banks. Beer bottles, spray-paint cans and cigarette butts regularly washed into beaver dams and up onto the banks.

In November 1988, the council organized its first cleanup on the edge of the city of Winters. Early on a Saturday morning, 60 volunteers gathered outside the gates of the city’s former sewage treatment ponds. Five hours later, they had towed out 11 rusty 1950s and '60s Chevys and Fords and filled 11 dump trucks full of mattresses, refrigerators and other debris. Putah Creek Council co-founder Susan Sanders remembers pulling out the carcass of a sheep. The story was mirrored up and down the stream. “The piece of ground I bought was a dump,” said landowner Dennis Kilkenny, who lives just outside Winters. “It was a legacy dump for everybody in the world.” Maybe that was the only bright spot when the creek dried up in 1989: at least then it was easy to pick up the trash. |

|

In August, after Camp Putah kids reported the dry creek, the year-and-a-half-old Putah Creek Council turned to the Solano Irrigation District. They begged Brice Bledsoe, the district’s manager, to release a little extra water down the creek.

Bledsoe, the director of the Solano Irrigation District, was part of an older generation of water managers who did not consider environmental releases a prudent use of water. Hired as a young engineer just a few years after Monticello Dam was completed, he came of age during an era of prolific dam building. Shasta went up in the 1940s, Monticello in the '50s, Oroville in the '60s. All followed President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1908 command to Congress: “Every stream should be used to the utmost.” The effects on rivers and the surrounding ecosystems were not considered. Bledsoe was, by all accounts, an impressive water manager. He became the district’s first assistant manager in the late '60s, and was promoted to manager half a decade later. Among other achievements, he catalyzed the construction of the Monticello Dam’s hydropower plant. As a testament to his influence on the region’s rivers, The Reporter in Vacaville named him the “water czar” in his 2005 obituary. In drought conditions, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation — which owned the Monticello Dam and leased it to the water agencies to manage — required operators to switch to a dry release schedule. In 1989, the Bureau made special exemptions for environmental protection, and Bledsoe consented to the council’s request. Because the Council wasn’t technically a customer, UC Davis agreed to sponsor the transfer of an additional 1,000 acre-feet of water for Putah Creek. The university would become a key ally in the council’s fight for water, as both a Solano County Water Agency customer and a Yolo County institution with investments in the creek’s education and recreation values. It was enough to keep the creek alive until the winter rains came. Though that winter was the wettest in three years, below-average rainfall wasn’t enough to break the drought. Where 1989 had been a dry year, 1990 turned critically dry. March, April, and May brought no more rain. In June, a cry rang out through the Putah Creek Council: The creek had run dry again. |

“During the summer of 1989, water levels in the creek on my property began to drop, and on August 2 and on August 3 all flow stopped. By August 6, long stretches of the creek were dry and fish began dying in remaining pools. Between August 6 and August 15, a small amount of water recharged the pools repeatedly so that fish in the deepest pool on my property survived until some of the water purchased by the Putah Creek Council and other agencies was released and saved the creek from drying out completely."

— Landowner Manfred Kusch, in a 1990 deposition to the Sacramento County Superior Court

— Landowner Manfred Kusch, in a 1990 deposition to the Sacramento County Superior Court

|

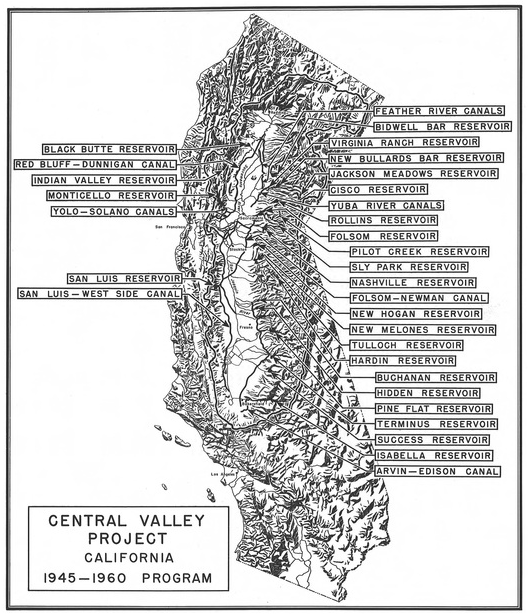

Monticello Dam is a child of bureaucracy, built by a federal agency, subject to state law and operated by local agencies.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built and paid for the dam in trust for Solano water users. It contracted with the Solano Irrigation District for the dam’s operation and maintenance, and the district and other consumers — like Solano County cities — signed individual water contracts with the Solano County Flood Control and Water Conservation District, which contracted for the water directly from the bureau. As these customers paid the conservation district for water, they also were paying off the initial construction debt. Eventually, Solano interests will own the dam. In 1988, local interests hoped to fast-track that ownership by paying off the remaining debt up front, so the district, cities and other water interests banded together to form the Solano County Water Agency, a second life for the conservation district managed by its members instead of the county’s Board of Supervisors. It took over the dam’s operation and maintenance, and became a water wholesaler for its members and for UCD — the only Yolo County customer. But they aren’t the only ones with a say in how the dam is operated and its water is allocated. The total amount of water available for use each year is limited by the California State Water Resources Control Board; in Monticello’s case, the Bureau of Reclamation has 207,350 acre-feet to allot. |

|

As Putah Creek browned, Congressman Vic Fazio took the floor of the House of Representatives and introduced a bill that would allow the SCWA to purchase Monticello Dam for $28 million.

Fazio, a powerful representative in the fifth of his 10 terms, believed SCWA had every interest in keeping the dam and reservoir in excellent condition: Its consumers demanded as much. Besides, the agency already operated and maintained the dam and Lake Berryessa provided water almost exclusively to Solano County. It was the “Solano Project,” after all. He approached the Putah Creek Council for its support. At first, the leadership hesitated. But, after Fazio guaranteed some protections for the creek, it signed on to back the bill. As 1990 turned grim, the council turned to SCWA and Bledsoe, asking for more water for Putah Creek. The council expected goodwill from the institutions that had promised local control would be better for the dam. “There were kids coming all the way up the creek bed on dirt bikes,” said Manfred Kusch, who owns 22 acres of land halfway between Davis and Winters. “It was bone-dry.” A photograph from the first set of depositions show his young son playing in the cracking mud. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation didn’t have the same environmental allowances as it had in 1989, so the Solano agencies denied the request for water. The State Water Resources Control Board’s water limits wouldn’t allow for more releases down the creek, Bledsoe argued. And the board refused to hear the council’s case. |