|

The kids at Camp Putah found them first, the dead and dying fish flopping on the muddy creek floor. Most summers, eight campers and a counselor would pile into 17-foot aluminum Grumman canoes and paddle down a wide stretch of stream along the edge of the UC Davis campus.

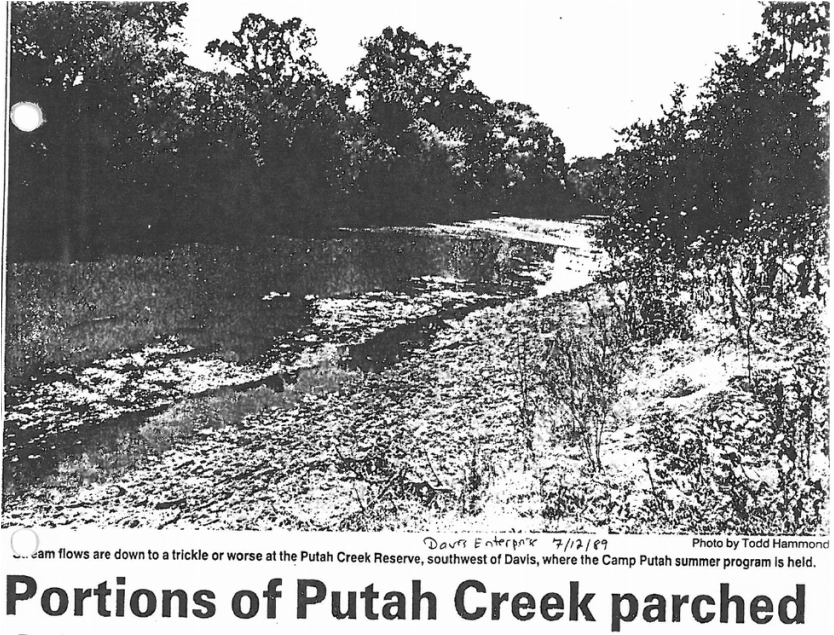

But in the summer of 1989, California found itself in the middle of a lengthy drought, its third of the twentieth century. As the summer days lengthened, the state grew thirstier. Reservoirs sank into themselves. Corn withered in the fields. When news that the creek had dried out reached Steve Chainey, a 39-year-old restoration ecologist, he rushed over to its banks to see the destruction for himself. The stink wafted upwards. Fish and oyster carcasses littered the floor of the creek, rotting in the withering sun. “It wasn’t just not flowing, there was nothing but drying mud for miles,” recalled Chainey. A year prior, he and Susan Sanders, a wildlife biologist, had founded the Putah Creek Council, a community environmental group that so far, had hauled trucks and trash out of the water, planted oak saplings and organized bird-watching outings. Now, the Council found itself without a creek. “That was the beginning of a very long journey—much longer than I thought it was going to be,” Sanders said. Within a year, the Council would find itself embroiled in a decade-long lawsuit over water rights. But what began as a contentious battle became something different: a glimmer of hope in a state that is again suffering from drought. Because today, the creek has water — and so do the farmers, the cities and other neighbors that share its watershed. As hundreds of other communities in California face a water scarce future, Putah Creek could serve as a model for how to stretch limited water resources further. |

|

Far west of Davis, Putah Creek pours down from the eastern slope of Cobb Mountain, the tallest of the Mayacamas. For millions of years, it dropped out of the Blue Ridge through Devil’s Gate, a narrow sandstone canyon, and spread out its tendrils, gathering run-off and channeling the water from 576 square miles of land, before emptying into a swampy channel that eventually washed into the San Francisco Bay. It’s one of the numerous streams that fed the Sacramento Valley, flooding and mixing its soils into the nation’s salad bowl.

For the most part, the creek flowed year round, drying up in a few places during prolonged droughts, but kept perennial by underground aquifers that pushed cool groundwater into its channel. Nowadays, it pools at the Gate to form Lake Berryessa, the eighth largest reservoir in the state. The floodgates of Monticello Dam dictate the life of the eastern half of the creek. Eight miles down, a second, smaller dam diverts much of the water south to Solano County's cities, farms and industry. Together the pair of dams are called the Solano Project. Putah Creek defines the border between Yolo and Solano counties, but Yolo communities like Davis and Winters opted out of the reservoir’s water 50 years ago. For Yolo County, Putah Creek is a refuge of habitat and recreation. For Solano, it is the tail end of their primary water supply. The water leftover from the project forms Lower Putah Creek. Landowners with riparian rights take their share; the rest flows out the Yolo Bypass. In 1989, after two critically dry years, Putah Creek’s flow into Lake Berryessa slowed to a trickle. The Solano County Water Agency and Solano Irrigation District, which control the Monticello Dam, triggered the reservoir’s drought schedule. Lower Putah Creek was the only downstream recipient whose flows were reduced that year; others saw cutbacks in following years. Depleted groundwater aquifers sucked water into the ground. Allegations flew that some farmers were illegally diverting the creek to water their crops. By August, the creek had gone dry. |

|

Before the Council, the lower half of Putah Creek had existed for a century as barely an afterthought.

By the late 1800s, most of the native people, known as the River Patwin, had been driven out by ranchers and pioneers who sailed in from the west and rolled in from the east, lured by gold, land and freedom. Originally, Putah Creek ran through the center of Davisville, but winter flooding exhausted farmers. Homesteaders took their donkeys south of the town and dragged plows through the ground to dredge the South Fork, diverting the river past the town. Records show the levees failed multiple times, carrying off houses in both Davisville and Winters, but eventually the river settled into its new channel. This was the first of many adjustments made to the creek. The rerouting straightened its course, causing it to run faster and cut 10 or 20 feet deeper into the soft dirt. Years later, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reinforced the levees with concrete. The isolated remains of the North Fork form a pond-like system maintained by the UC Davis Arboretum. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation began eyeing idyllic Monticello Valley for a reservoir in the early 1900s, to supply irrigation and drinking water to local military bases and a booming Solano county. Congress finalized the decision in November 1948; construction began in 1953. Photographers Dorothea Lange and Pirkle Jones chronicled the dismantling of the sleepy hamlet in “Death of A Valley.” Devil’s Gate was locked tight in 1957, sealing off the lower third of Putah Creek from 90 percent of the watershed. Lake Berryessa would take six years to fill; at the time, its 1.6 million acre-feet of storage made it the second largest reservoir in the state. It remains one of the longest, extending 15.5 miles through the valley, just under a quarter of the full stretch of the creek. The reservoir, by all human accounts, is an astounding success. It provides flood control, recreation and a reliable water supply in times of drought, like these last three years. But Monticello and the Putah Diversion dams cut off Lower Putah Creek as casually as one might snip off a flower stem. Pitted by gravel mining operations and overrun by aggressive invasive species, it had been all but written off by state agencies. If it didn’t flow all the way to the bypass, no one noticed. No one was watching. In 1989, Steve Chainey and the Putah Creek Council were watching. |