|

Putah Creek’s transformation has been dramatic, but it would be little more than a footnote in California history, except for one tireless champion: Peter Moyle, an affable and energetic ichthyologist on a quest to rescue California’s native fish from almost certain catastrophe.

Moyle had testified in the Putah Creek Council’s trial, detailing the ways in which Monticello Dam had choked out native fish populations and allowed invasive species to thrive. The judge’s ruling in favor of the creek hinged on Moyle’s testimony. So did the Putah Creek Accord: Moyle drew up the flow regime that the two sides finally agreed upon. While the creek got more water, the new flows were just a fraction of the historic volumes. But Moyle believed that it wasn’t how much water that mattered — it was when and how they used it. |

|

Moyle grew up on the banks of Minnesota’s Lake Minnetonka with a fishing pole in one hand and a magnifying glass in the other. He’s got water in his blood: His father was a fish biologist, his mother an aquatic biologist. He gutted fish for breakfast while learning his multiplication tables.

After Moyle earned his doctorate in zoology at 26, he drove out west to Fresno State University; it was the warmest place he’d been offered a job. As a junior professor, he had a research budget of exactly zero dollars. So on the weekends, he and one graduate student would hop in his van and drive up and down the Central Valley to investigate the local fish species and collect specimens for his class. “When you got down onto the valley floor, the lowest part of the valley, you had the same fish you found in Minnesota,” Moyle said. All bluegill, large-mouth bass, golden shiners and catfish: invasive species brought west on the railroad by specially designed fish cars in the late 1800s. But when Moyle started roaming the low foothills, he caught blackfish, hardhead and pike minnows — fish “that nobody else knew anything about.” “Anyone who was smart went up to the cool Sierras to study trout or the coast to study salmon,” Moyle said. These native California fish had been isolated from the rest of the country by the rise of the Sierra Nevada Mountains 4 million years ago. Trapped in a region prone to massive floods and prolonged droughts, the relatively few species that survived evolved specifically for these extreme conditions. “There’s nothing else like them anywhere else in the world,” Moyle said. He quickly earned a name for himself as an expert on endemic fish. UC Davis hired Moyle out of Fresno just three years after he arrived. In the past 40 years, he’s become the foremost expert on California’s inland fish. |

|

Of California’s 175,000 miles of river, half is diverted or impounded for urban and agricultural use. These dams reduce the risk of floods and store important water reserves for a thirsty and drought-prone state.

They also block access to almost three-quarters of the historic habitat of migrating fish like salmon and steelhead and flatten out water releases, eliminating the high flows many invertebrates need to trigger spawning. Through all the waterways, native fish fight against 50-some invasive species for habitat. These alien fishes are often better adapted for the monotone flows of a dammed system than the California natives. It’s a one-two-three punch: the dams, the invasive species and the amplifying effects of the two together. In the 1990s, Moyle and then-graduate student Michael Marchetti began exploring ways to undo this damage. One theory, which restoration ecologists were beginning to discuss, was releasing water to match the natural water patterns of a system. Colorado ecologist LeRoy Poff published a seminal paper on the idea, dubbing it “natural regime” management, in 1997, and the idea found its way into the Putah Creek Accord negotiations. California’s Mediterranean climate and varied geography means its rivers and streams follow patterns of flooding and drought: the “natural regime” of the system. These, of course, vary from year to year, but trend toward a particular pattern. Fish, mollusks, trees and grasses evolved according to this rhythm, counting on the staccato and rests for certain life-cycle events like breeding, seeding or migration. When a stream is dammed, the music of the flows are typically reduced to two notes: high in the summer, low in the winter. Water was released on schedule, according to human needs, completely out of tune with the ecosystem. These practices destroyed native populations. The natural regime theory predicts that native species will thrive in a system that mimics the music of their evolutionary environments. As it turns out, the timing of the pulses is far more important than the amount of water. |

|

For example, many native fish spawn in the spring as streams swell with the snow melt. When a dam blocks the extra water from coming down stream, the fish don’t get the signal that kicks their natural instincts into gear. With a couple of well-timed releases from a dam — mimicking a couple of days of high flows— those fish are much more likely to spawn and to do so successfully.

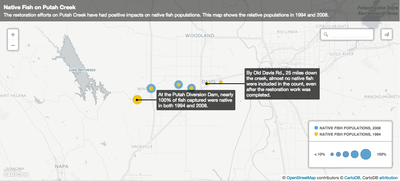

“It’s water they need and what they respond to,” Moyle said. Moyle based the flows in the Putah Creek Accord on the natural regime idea. The settlement requires the Solano County Water Agency to maintain certain speeds of water flow, hinged around two high water pulses in the winter and spring. Rarely do scientists have access to data taken about fish populations before and after the practice is implemented. But Moyle had been surveying the creek since 1991, and periodically before that. A decade after the accord, he and his colleagues sat down to see if the native fish had actually benefited from the flows. “It’s crazy when something works out quite so well,” said Joe Kiernan, a postdoctoral researcher at UCD who published the paper with Moyle on the success of the theory in Putah Creek. “It was such a clean story.” Native fish populations had made remarkable recoveries, gaining toeholds 13 miles downstream from the diversion dam in eight years. (The data ran from 1991 to 2008.) In the warm and slower-moving water the rest of the way, from Old Davis Road to the Yolo Bypass, invasive fish maintained dominant populations. Putah Creek is the first waterway to prove that natural regime theory could be used to restore fish populations. The result? Moyle’s flows succeeded with just 5 percent of the water that would naturally flow down the creek. "Peter’s work is the best work out there that shows how natural flow regimes support native fauna,” said Poff, the scientist who wrote the paper on natural regimes. And it wasn’t just the fish that thrived. “Once you've got water back in the creek for the fish, everything else followed,” Moyle said. “The whole biodiversity exploded in the creek … once it became set up to favor native species.” There is a caveat, a big one, Kiernan said. Lake Berryessa spilled over into the Glory Hole in 1997 and 1998, sending massive waves of water down Putah Creek that likely destroyed many of the invasive populations. “I don’t know if it would have been so clean if there hadn’t been these true natural events,” Kiernan said. “If they (invasive species) had a stronghold anywhere, that sort of wiped them out.” The floods washed them out; the natural regime flows kept them at bay. |

|

Around the same time as the Putah Creek trial, Moyle took another oath in another courtroom to fight for the endangered Chinook salmon in the San Joaquin River.

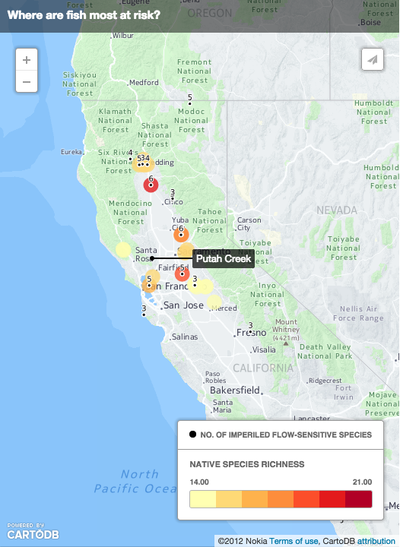

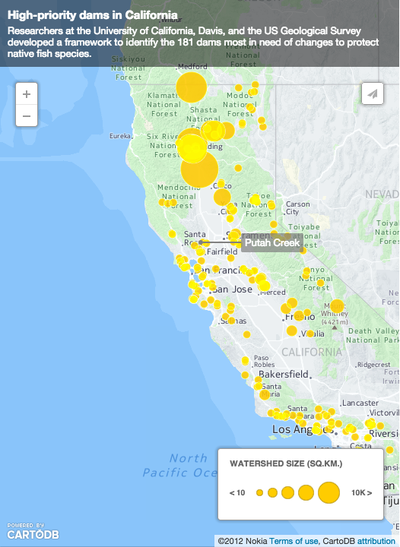

The San Joaquin is the second-longest river in California and supplies thousands of farms and cities with water. The section under contention was eight times bigger than Putah Creek. Prior to the construction of the Friant Dam in 1946, tens of thousands of Chinook salmon swam up the river and spawned. Before they had a chance to return to the sea, despite protests from the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation turned off the water. Fifty-thousand baby salmon died. In 1988, just before Putah Creek ran dry, two nonprofits sued the bureau over that stretch of river. The case took 18 years, through negotiations, trial and settlement. Moyle was the star witness, his testimony based on his experience with Putah Creek. In 2006, a final ruling — with flows based on the Putah Creek Accord — gave the San Joaquin back its water for the first time in more than half a century. Armed with ecological proof from Putah Creek and the victory in the San Joaquin, Moyle is now taking on the whole state. Last year, he published a study that shows climate change and human activity could drive 82 percent of native California fish to extinction by the end of the century. Adopting a natural regime release schedule could help save those fish, and it would be much easier to do it sooner rather than later, before fish gain endangered status. But Moyle needed a way to identify the dams most likely to be harming downstream fish. He teamed up with Ted Grantham, a U.S. Geological Survey researcher who was a postdoctoral student at UCD, until 2012. In October, they released a report that identifies 181 of California’s 1,440 dams most likely to be threatening fish populations and violating Fish and Game Code Section 5937. The sheer number of dams in California has made the task of individual evaluation a pragmatic impossibility for state agencies. Grantham looked at the health and richness of native fish populations near a dam and how many species have disappeared from the environment around the dam. He also compared the size of the dam to the amount of water that naturally flows through the system in a given year. Dams that impounded more water than actually flowed in through the system tend to, unsurprisingly, send little water downstream. Moyle and Grantham hope the report will help the California Department of Fish and Wildlife examine and more thoroughly monitor dams. They have reason for optimism: DFW’s current director, Charles Bonham, used to head the California arm of Trout Unlimited, which works to protect and restore fish habitat. One of the biggest problems identified is that many of the state’s dams have no gauges to record data about the water flows released and no even fewer have access to downstream surveys of fish populations. That dearth of information makes it impossible to determine if Section 5937 is actually being violated around the 181 “at-risk” dams. |

Explore the data

|

However, the report has received a muted response. As of Thanksgiving, the Department of Fish and Wildlife responded that no one could comment because they had not read the report; no inquiries were returned after the holiday.

Two nonprofit groups helped fund the study — the National Resource Defense Council and Trout Unlimited. Monty Schmidt, a representative from NRDC, said the most valuable of Grantham’s findings was how little data the state and his group have to work with. The California director of Trout Unlimited, Brian Johnson, said development of tools like these would strengthen its work in the future. But with the current drought, environmental groups are shying away from asking for water for fish. Moyle is undeterred, happy to keep trading in his galoshes and fishing bib for a suit and tie if he can help the fish. “I’ll keep after them. It’s our responsibility. If we don’t protect them, nobody else will,” Moyle said. This year, Putah Creek is once again proving that to be true. On Nov. 29, the first high flows of the winter were released down Putah Creek. By Dec. 8, researchers, the Putah Creek Council and landowners were all reporting the same thing. Footlong Chinook salmon — as many as 100 — had swum up the creek to the gravel beds below the diversion dam to spawn. Former Putah Creek Council board member Robin Kulakow noticed them as they left the Yolo Bypass, creek landowner Herb Wimmer caught some photos as they swam past his property, the Winters city manager found four at the park and Moyle’s students went out to survey them at their gravel spawning beds, right below the diversion dam. Putah Creek’s fish are finally coming home. Correction: California does not have two million miles of river, it has 176,000 miles.

|